Story Design - Story Telling pt.3

Sunday, July 3, 2011 at 4:43PM

Sunday, July 3, 2011 at 4:43PM Continuing with examples for each facet of story design...

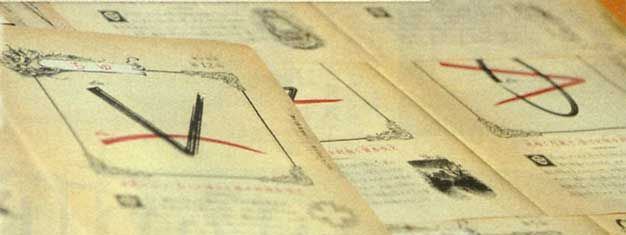

Pages from the DS game Ni No Kuni.

Execution

Efficiency. In general efficiency for video games is measured in both its narrative scenes and gameplay. To not confuse this facet with pacing, think along the lines of design space, art assets, and the number of elements of story content. If locations, set pieces, characters, scenes, etc. overlap in what they bring to the story, efficiency goes down. If you feel like a story begins to repeat its lessons, themes, or scenarios, consider if it could have gotten by with less. Tales of Symphonia is a game filled with many locations, characters, and scenarios that are very similar to each other both in their functional role (gameplay) and narrative role. Often in video games, a gameplay necessity will force a narrative inefficiency.

Coherence. The details of a story shouldn't contradict each other. One of the most well known ways for video game narratives to lose coherence is from ludonarrative dissonance. Like with efficiency, we know that the story content communicated through the gameplay can influence and conflict with the story content presented otherwise. Because video games are designed with varying levels of abstractions dissonant elements are very likely to occur. For example, in Final Fantasy 7, at the beginning of the game soldier shoot guns at the player characters. The damage dealt is only a small percentage of HP. Are we to believe that these guns are weak? These characters are armored? It's hard to say. In fact, many video games characters survive from a range of cartoon violence. Though we accept these abstractions and interpretations, it's hard to turn around and accept the death of a main character from a single bullet shot in a cutscene. These narrative bullets are even in games like Halo: Reach.

Pacing. For every wave, the climax is the result of building narrative and dramatic energy/tension. In terms of gameplay pacing, there should be a similar building of gameplay concepts or difficulty. And like the other facets of execution, we have to look at how the pacing of the story content and the gameplay match up. Might & Magic: Clash of Heroes features multiple chapters. In each, a new character is introduced starting at level 0. These chapters start out easy. As you progress you'll fight stronger enemies and eventually a boss. As the overall story builds, the gameplay difficulty resets several times throughout the game. This disconnect is most apparent at the final chapter. Instead of launching into the final battle, you pick up yet another new character and are forced to play through a long gauntlet of relatively easy battles.

Style/Language. The story scenes in Super Smash Brothers Brawl: Subspace Emissary and Super Meat Boy are presented in the style of silent films (see Brawl videos here). No dialog or text. Just visual storytelling. Final Fantasy 6 has a strong theater like presentation. Characters turn to the screen to emote opening up their bodies to us, the audience, via the screen. Each character is also introduced with their musical theme and a personalized description like you might find in a playbook. Other games borrow from the Japanese manga/anime style of storytelling featuring somewhat stilted dialog scenes that divulge lots of information. Examples include the Advance Wars series, Tales of Symphonia, and The World Ends With You. And of course there are the games that go for a movie like cinematic presentation from Uncharted, Heavenly Sword, to Halo: Reach.

Medium. I presented many examples of games that take features from other mediums in part 1 of this series. Because video game designers can basically pick and choose the kinds of medium-specific elements they want to incorporate, there isn't anything close to a singular scale of craft/design all video games are measured by. In other words, a modern game can feature voice acting or text based dialog. One isn't necessarily better than the other. I have to say this because many believe cinematic presentation is the singular standard that all games should aspire to.

Dynamic. Some games feature branching narrative paths and encourage the player to explore all the possibilities like Radiant Historia, Tactics Ogre: Let Us Cling Together, The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask, and Mass Effect. Some developers have discouraged exploring a game's story possibilities like Heavy Rain. These are well known examples. But remember even the warps in the Super Mario Brothers platformers dynamically change up the progression of the gameplay narrative. Along these lines most games wil have dynamic/emergent gameplay and therefore some level of dynamic narrative. So this category tends to refer to dynamic non-gameplay elements. Side quests are probably the easiest example of a dynamic ludonarrative feature.

Another image from Ni No Kuni.

Discourse

Creativity. All games are creative in one way or other whether we like the unique elements or not. It's nice to compare how unique and creative one work is compared to others, however this is an inherently difficult task. No one plays all the games out there, not even of a single popular genre. And even if one were to play many games, one can always study a work more deeply to uncover more of its story content. So, if understanding how creative a work is depends on how its details compare, you're quest will never end. Still, as long as we properly scope our comments (based on series, genre, etc.), we can talk about creativity. This is especially easy to do when identifying video game parodies. Linear RPG, You Must Burn the Rope, and Super PSTW Action RPG are all great examples. These games aren't very good gameplay and story wise if you don't understand that they're parodies. This guy didn't quite understand, and now we have a hilariously entertaining video based on his response. In some ways, being a parody gives these games a freebie. Fortunately, they're all short and to the point (efficient).

Series. The power of sequels and series is undeniable. In many mediums, narrative series and IP brands have significant selling power over new products. We love the familiar and we love knowing the full story. So, when games continue in a series many gamers enjoy connecting the details. Likewise, many gamers get very upset when they don't line up. There are some that try to piece together the story of all the Zelda games even though they're not intended to be a narrative series. Some argue over Metroid canonical content even including odd games like Metroid Prime Hunters and Metroid Pinball into the grand storyline. This facet is basically coherence across multiple independent stories.

Transmedia franchises. Halo is a popular video game series. The franchise also includes a collection of animated shorts, comics, and novels. There was even a rumored movie in the works. All of these products work to support the detailed overarching Halo universe. Dead Space, Pokemon, Zelda, and Metroid are also transmedia franchises.

Resonance (Harmony)

Aligning a game's narrative and gameplay is the most difficult and effective way for a video game to create resonance. Still, one can create resonance between any two facets of a story. Typically, theme is more likely to resonate with each of the other facets. Because themes are so abstract, there more flexibility matching it up with concrete elements like setting, characters, and plot actions. I particularly appreciate the resonance between the poetry text presented in Braid and its gameplay. The poems tell the story of Tim's past filled with love, loss, and longing. These abstract concepts resonate with the kinds of challenges and mechanics in the gameplay. For example, regret is paired with the idea of wanting to go back and fix things; a do over. In the gameplay players have the power to rewind time to fix things with few limitations. From here the richness of the resonance invites us to consider Tim's character through his gameplay actions of solving puzzles. Is he wiser now? Can we ever really get a do over?

In part 4 I address a bias people have when thinking about stories.

Reader Comments