Listening to episode 47 of the Retronauts podcast I was reminded of common communication crutch that many use when trying to expound extemporaneously or otherwise about video games. "[insert game here] is greater than the sum of its parts."

How is it possible for a video game to be greater than the sum of its parts? All video games can be broken down into parts. Basically, a game is made up of various elements (audio, mechanical, visual, level, enemy, player, etc). So, if we start with a whole game, break it down into parts, then put it back together how is it possible to end up with more game than we started with?

More often than not, when "greater than the sum of its parts" (GTTSOIP) is used the speaker is unable to explain what the parts are or the composition of this greater "sum." Like reading a tricky poem or watching a convoluted film, the type of person who has yet to understand the work will opt to respond saying something along the lines of "that poem/movie was too deep for me." Unfortunately, such a statement does nothing toward brining a works depth or other substantive content to light. And in the case of video games, instead of admitting that one doesn't understand a game fully, many opt for the GTTSOIP phrase.

Perhaps I'm not giving these GTTOSIP users enough credit. What if "greater than the sum of its parts" was a way for someone to attempt to explain counterpoint a high level concept in and of itself? Take a look at this excerpt from wikipedia on counterpoint and development.

A melodic fragment, heard alone, makes a particular impression; but when the fragment is heard simultaneously with other melodic ideas, or combined in unexpected ways with itself (as in a canon or fugue), greater depths of affective meaning are revealed. Through development of a musical idea, the fragments undergo a working out into something musically greater than sum of the parts, something conceptually more profound than a single pleasing melody.

So if counterpoint in video game theory is similar to counterpoint in music theory, then shouldn't this phrase be apt for describing games such as Super Mario Brothers, a game featuring counterpoint that I've already detailed here on this blog?

My response is still no. To assume quite a bit of credit onto whoever uses the "GTTSOIP" phrase, the multitudinous and unexpected ways a game can achieve depth through counterpoint is still a part of a game's elements. Emergence and counterpoint don't exist in a state removed from the game. They ARE a part of the game. Therefore, to pretend that they're distinct and separate for the purpose of making a statement about the overall "sum" of a game is counter intuitive, counter productive, and simply counter (to the) point.

Functionally, "GTTSOIP" is analogous to "niggles aside" a phrase used when a reviewer attempts to reduce, trivialize, and skirt a game's shortcomings only to highlight a game's pros, which in turn bloats the credibility and valitdity of the statement/article in the end. The Mass Effect Game Informer review is just one example of many with "niggles aside" writing. If you listened to the episode of Retronauts, GTTSOIP was used in close proximity to honest statements that uncovered the bad gameplay elements of a game called ActRaiser. These gamers, having backed themselves into a corner, tried in one last attempt explaine their appreciation for a game they had just previously cut down by using the GTTSOIP phrase.

After reaching the above conclusions about the use of GTTSOIP, I began to wonder how so many people could so obviously overlook a game's faults to create a disproportionate play experience of a game in their own minds. That's when it hit me. More often than not, it's not that people are actively ignoring a game's faults when trying to piece together the experiential or emotional impact of a video game. Rather, they don't remember the shortcomings because of how the static space created from the game's shortcomings allowed the player to switch to "auto pilot" or as I like to say "turn their brains off."

It's not difficult to find a gamer who loves RPGs. In fact, most of the gamers I know reflect fondly on at least one RPG from their childhood. Final Fantasy 6 and Pokemon Pick-a-color are two of my favorites. Even as I think back on them now, a wide grin spreads across my face. But the inescapable truth is, because these games are RPGs that feature random battles, I know that there was a lot of static space of attack-attack-healing random monsters that server neither to advance the story or as a distinct, unique challenge. RPG's like this are designed to consume time. Of course I don't remember using Crono's Luminare attack or Mewtwo's Physic attack hundreds of times in every battle just so I could get from one area to the next. Of course I don't remember grinding on monster to level up my characters. Of course I don't remember getting lost and spending hours wondering what to do next. My brain was turned off. But I do remember when Frog split the mountain in half and when I fought my rival at the end of the elite 4. Such events placed special markers in my gaming childhood.

See what I mean? If I includ all that "mindless" static gameplay into my assesment of either game, my "sum of the parts" assessment wouldn't be as immaculate and as glowing compared to a cursory look through my memories.

Like in the recent Arby's commercial, when people say "you do the math" there usually isn't any math to be done. Likewise, the utterers of GTTSOIP, I assume, haven't done anything close to breaking down a game into it's parts and adding them together according to some kind of clear, stable value system. But what if they did?

Here's the point in the article when things get just a little bit graphic.

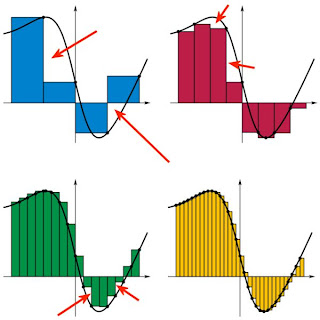

Figuring out what a video game is or what it's made of is like finding the area of a shape. But games are far from simple, and figuring out what constitutes a game is like finding the area under a curve.

See how the blue area has large gaps? These gaps represent inaccuracies in video game assessments. As the dividing bars get smaller and smaller, the gaps are reduced. In other words, as one's understanding and language of video games is broken down into smaller parts (like from functions to mechanics to qualities such as direct/dynamic/intuitive/individual) the accuracy and effectiveness of one's statements increases.

Problem solved.